An Immigrant Story, Part 4: The Restless Ghosts

The stories that we carry can haunt or liberate us.

If you have not read “Part 1: The New World,” “Part 2: The Escape Attempts,” or “Part 3: The Greatest Fear,” then start there.

An Immigrant Story, Part 4: The Restless Ghosts

The occasion that prompted my divulging occurred in our sophomore year’s Leadership course. Whereas much of the four-year Leadership, Ethics, and Law curriculum was methodical or doctrinal in nature—navigation or law, for instance—this class focused on ethics and morality. We discussed leadership principles and real-life situations that would challenge them. This new curriculum was born during the Academy’s Congress-mandated soul searching following the biggest cheating scandal in the school’s history, in which 24 members of the class of 1994 were expelled and about 125—fifteen percent of the class—were implicated in a scheme that involved an Electrical Engineering exam. The judgments from the “Double-E Scandal” had been fodder for national news just six months before my class reported for our Induction Day.

The class of 1998 was the first to experience this new curriculum, which sought to instill a clearer sense of right and wrong and, more important, the processes involved in determining one from the other. Where applicable, the syllabus inserted case studies from the fleet for debate. I loved those philosophical discussions, as they provided variety to a required engineering and technical core curriculum. One case study, however, hit close to the bone and rendered me near silent throughout the class meeting.

The instructor showed a 60 Minutes segment about Captain Alexander G. Balian, the former commanding officer of the U.S.S. Dubuque. In early 1989, the Navy court-martialed Captain Balian and found him “guilty of dereliction of duty for failing to provide adequate assistance to a group of Vietnamese boat people adrift in the South China Sea” in June of the previous year.1 The ship was steaming from Japan to the Persian Gulf when it encountered the refugee boat. The captain ordered the Dubuque to heave to at 500 yards away to assess the situation, and he deployed a whaleboat with a scouting team, led by the executive officer, to approach the junk. Seeing the ship had stopped, three of the refugees jumped into the water and swam toward it. When they reached the naval vessel, one of the men attempted to climb a monkey line used during the lowering of the whaleboat. Captain Balian ordered his sailors to shake off the intruder and directed the three exhausted men to swim back to their boat.

The court martial’s prosecutors argued that the captain had made poor ethical decisions. He had ordered the executive officer not to board the junk, and the entire inspection comprised about ten minutes of circling the Vietnamese boat and the shouting of instructions through a megaphone. When the refugees screamed back in English, “No engine! No engine!”—to say the engine had died—the executive officer reported to the captain by radio that the junk did not leave Việt Nam with an engine at all. The only method of propulsion it had, as deduced by the captain at a distance, was the 12-foot tall triangular sail that sat at the bow of the boat, which was at least 50 feet in length. A photo taken by an American sailor on the ship showed the whaleboat positioned next to the junk, and the 30-foot Navy craft looked just about half the junk’s length. Using insufficient information, without attempting to clarify or verify it, the captain deemed the decrepit-looking junk “seaworthy” and gave the refugees inadequate supplies to make the journey to the closest land, which he estimated would be two to three days. The allegations against Balian and the result of the court martial had been widely reported by the Associated Press and in national newspapers, including the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, and the Washington Post, before Balian went to CBS to tell his side of the story.

The allegations got so much press probably because the Vietnamese refugees who survived told a harrowing story of resorting to eating human flesh to stay alive. Fifty-two of the original 110 lived through the ordeal, and 30 of them perished after the encounter with the U.S. Navy ship. They had been adrift for 19 days before meeting the Dubuque (a fact Balian apparently did not learn) and for another 18 days after. Months later, after the trial had concluded, Diane Sawyer appeared on camera with two of the survivors, all of whom were eventually rescued by a Filipino fisherman and placed in a U.N. refugee camp in Bolinao. One of the men told Sawyer that a former South Vietnamese soldier had taken control of the boat, and he would select and kill people too weak to fight back, cut up and boil the body parts in seawater, and distribute the flesh to everyone. The victims included a 15-year-old girl and an 11-year-old boy. The man said the soldier told him he would be next, but on the following day they were rescued.

Today the Academy still teaches the course, called Moral Perception, and “Rescuing the Boat People” remains a popular case study and comes early in the syllabus.2 According to one senior instructor, the real-life scenarios are “visceral and allow the [students] to feel—not just know—the moral concepts that they may face” in the first few years as young officers and thereafter.3 With the Dubuque episode, we were asked to consider not just Balian’s options but also ours as junior officers if faced with a similar situation under such a commander.

My memories of that day are spotty, but certain odd details stand out, such as where I was sitting in the room. Before looking it up for this writing, I could still envision the b-roll footage of the captain in his summer whites walking along a pier with the correspondent. I did not talk much in that class discussion, that I know. As others hotly debated the captain’s decision and the fairness of the Navy’s judgment, I thought about the fate of the refugees. I felt sorry for them, that so many of them died unnecessarily. Until that day, I had purposely avoided watching or reading anything that reminded me of the ordeals of so many Vietnamese. Had we succeeded on any of our attempts to get to the South China Sea, my family and I could easily have been some of the people looking emaciated and desperate on the TV screen, or much worse.

Like other Vietnamese with similar stories, my family rarely talked about our escape attempts. Not many people did, even those who prevailed. Most of the time these stories were told about us. We saw ourselves in programs such as Family Ties and 60 Minutes through an American lens and, therefore, as outsiders. The absence of stories and explanations by Vietnamese, both in American culture and among the Vietnamese community, allowed people my age to deny and maybe even forget an undesired past. I was twenty years old then, six years after adopting the name Steven. Even as a fully acculturated American and a sophomore at the Naval Academy, seeing the images of a dilapidated wooden vessel packed with barely alive men, women, and children unburied a deeply rooted and irrational sense of shame. Sitting among my peers, I was far removed from the uniform I was wearing, a symbol of the most powerful navy on the planet, and felt only my heated skin and the insecurity rising underneath—the fear of getting caught wanting to belong. Either on that day or shortly after, I told my two roommates about my family and how watching the 60 Minutes segment affected me. (After freshman year, Dave and I were assigned to different companies.)

I could not recall exactly how the subject came up, and neither could I recollect much about the conversation, except a general feeling of dread and that one of them expressed surprise at not knowing until then. I did not receive the judgment that I had imagined they would inflict, not even a trace of it. When I recently asked the surprised roommate, Kevin—who had hosted me in Indianapolis during Le Mobile Feast—he remembered only that it took me several tries to get the story out.

I know now that this fear stemmed from the same irrational shame that prompted me to develop a Southern Vietnamese accent in Sài Gòn and a native English sound here. I was afraid of being seen as not just an outsider, but also a người nhà quê. The Vietnamese term means “country person” or “peasant,” best translated to English as “hillbilly.” We use it almost always with derogatory connotations: a boor, or an unrefined or ill-mannered person. Someone can possess the countenance of a người nhà quê, or dress or sound like one, or behave as one. In practical use, it applies equally to someone actually from the countryside as to a newly arrived immigrant to a Western country who might have spent his entire life in a city, but who now appears as lower class to the acculturated sense and sensibilities.

As a child, my self-consciousness took root in the worry that others might see me as a người nhà quê, especially Vietnamese Americans who had been here longer. For example, even if my fifth-grade friend Steve did not see me as a người nhà quê, I perceived myself as one when standing next to him. Even as an adult I could feel remnants of that dread while looking at the birthday photo of us together. My donated clothes did not fit like his, and our home that was filled with garage-sale furnishings loudly announced that we did not yet belong. Those young roots would bear branches that made me, even as a young man, unable to empathize with (different from feeling pity for) many Vietnamese immigrants who escaped by boat and came here from refugee camps. I know now that I rejected them because I was determined to evade my own past and any emotional identification with it. The most expedient way to accomplish this was to denounce “them” and to believe that I have earned my place above them.

Like Jay Gatsby, I had run away from what I thought would trap me. In the novel, he dies before getting a chance to reconcile with it, but the past would not let him escape completely. Although hundreds of people attended his parties while he was alive, none of them show up at his funeral. Other than the narrator and a few obligated servants, only his father—the person Gatsby most wanted to disassociate from—comes to pay respects. Unlike Gatsby, I would eventually learn to see and feel differently about my own past and the shared history of the Vietnamese diaspora. But that process would not even begin for another decade, when I was in my thirties, and at around that same time the survivors of that boat got to tell fuller versions of their stories.

In 2007, the Vietnamese American nonfiction storyteller Đức Nguyễn produced the documentary Bolinao 52, so called for the number of survivors. The newspaper articles with the gruesome mention of “cannibalism” first grabbed his attention, but it was the same 60 Minutes segment that prompted him to conclude that the victims’ stories were incomplete.4 Filmed within a year of the horrific event, no full story could have been told, as the refugees were still reeling in the trauma. Answering Diane Sawyer, one unnamed survivor could not look into the camera or at her, his eyes welling up with tears. He fidgets and darts his eyes side to side and downward, and with a shaking voice, he says, “I don’t want to be reminded anymore about that trip.” Even Nguyễn’s family opposed his film project, afraid that it would bring shame upon the survivors.5 Himself a boat person whose family was rescued by an American ship after just four days at sea, Nguyễn felt a connection with the survivors and understood that only luck had dealt their wildly different fates.

The first person Nguyễn located was living in Orange County’s Little Saigon, and he turned out to be the man who had tried to climb the monkey line and was shaken off by the American sailors. He declined to be interviewed on camera, so Nguyễn subsequently narrated the information obtained during an unrecorded conversation. Xuân (no last name given) had been a lieutenant colonel in the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) and likely had fought alongside American troops. After Sài Gòn’s fall he spent 14 years in “re-education.”6 After his release, he experienced the same push factors that my dad spoke about: his father also endured five years of prison, and the government had confiscated their house. Seeing no future for himself and his family, he persuaded his sister and others to attempt an escape by sea. Less than two months after completing his long prison sentence for fighting on the same side as American soldiers, Xuân was abandoned at sea by American sailors. Although he refused to be recorded, Xuân introduced Nguyễn to his sister, Tùng Trịnh, and hers would be the main narrative voice in the film.

Bolinao 52 opens with Trịnh conducting a memorial service on the sands of Bolinao for the 58 people who had died. It had been 17 years, and Trịnh was traveling outside of the United States for the first time since she resettled there. She had vowed not to go anywhere else abroad before returning to the fishing village in the Philippines to lay ghosts to rest. In one segment Trịnh was joined by her son, Lâm, who at the time of filming was a U.S. Marine. He was five years old on that boat (around the same age I was during my family’s many escape attempts) and remembered only that he had eaten toothpaste to stave off hunger. His memory had spared him the gruesome details that his mother had also hidden from him for more than a decade. Until late in high school, Lâm had forgotten almost everything about the journey; his cousin discovered the CBS story and asked him about it.

The film follows an arc of redemption, as Nguyễn was able to introduce Trịnh and her son to one of the sailors on the Dubuque. William Cloonan was a chief petty officer at the time and believed that Captain Balian had made an immoral decision to leave the refugees behind. Although he had seen the survivors on 60 Minutes, he had never met any of them until Nguyễn offered to introduce him to Trịnh and her son. The meeting occurred in a hotel lobby, in Japan, where Lâm was stationed at the time and where Cloonan happened to be living. Both were interviewed separately before the meeting. Trịnh said that she wanted to understand how the Americans could just leave them to die, and Cloonan was anxious and afraid that he would not find the forgiveness to clear the guilt he had carried for 17 years. During their first encounter, he explained to her and Lâm that many others on the ship felt as he did, but the situation was out of their hands. Being a U.S. Marine, Lâm confirmed for his mother that the military chain of command would make that the case. After her son had returned to his base, the film crew followed Trịnh and Cloonan as they spent a day together walking around town and seeking reconciliation in conversation and fellowship. In one moment, the two held each other’s hand and appeared overwhelmed by emotions.

Following the film’s screening in 2008, Trịnh told an interviewer from KQED that her brother Xuân had advised her against participating in the project. “Keep things in the past and let them go away,” he said, echoing the Vietnamese sentiment all too familiar to me.7 But she could not let them go, and the ghosts haunted her for 17 years. Sharing her story, meeting Cloonan, and returning to Bolinao helped her to transform the pain. After the film’s release, more survivors contacted Nguyễn and wanted to talk.

“They felt that what happened on the boat was a very shameful chapter in their lives and were unable to talk about it because of the taboos,” he said in the same interview. “Once Tùng Trịnh was able to reveal her story, others felt relief because their story has been told.”

While some people wished to share their stories and confront the past, others preferred to ignore it and move forward. During the unrecorded interview that Nguyễn conducted with Xuân, he asked about Captain Balian’s decision to leave the refugees behind. Xuân referred to his own military experiences and said that he understood the captain’s responsibility to his orders. Sitting outside an American coffee shop almost two decades later, he claimed to have no hard feelings toward the captain or anyone on the Dubuque. After all, he said, the ship did stop and render some aid, unlike any of the other two dozen ships that just passed by (none of them was another American ship.) Although I understood Xuân’s perspective and rejoiced at the peace of mind he seemed to have found, I thought that his answer to another question revealed some unresolved tension. When Nguyễn asked Xuân about the men who took charge of the boat, he replied that “he doesn’t know those people and doesn’t recall anything about them,” as recounted by Nguyễn.8 Either he had truly let the past “go away,” or he was evading the pain.

To lay ghosts to rest—I used that phrase to describe what Trịnh was seeking to do upon her return to Bolinao. The phrase comes from rural South Africa, where the forced removal of indigenous peoples during the apartheid era created fertile ground for stories of anguished souls that cannot find peace in the afterlife. People sometimes performed a ritual to lay the ghosts to rest, usually involving an elder who would call each ghost by its name and plead with it “to make peace with whatever unfinished business was troubling it.” Until called upon by name and confronted, so goes the belief, these ghosts would continue to haunt the living.9

Disclosing dark personal stories, especially in the context of a shared traumatic history, allows us to confront the ghosts, to call them by name. Unlike the morality tales and folklore that my grandmother used to ease us into slumber or the neatly packaged sitcoms that also attempt to instruct as well as entertain, sometimes the stories we most urgently need for healing are messy and unresolved. They convey pain and losses without offering any soothing balm. They deny us an easy discernment of right and wrong. Instead, they contain nuances and contradictions, making it difficult for us to tell them cohesively and to receive them so as listeners. I had a hard time writing this story because I still harbor some ghosts whose names I cannot yet say or perhaps do not even know. Once I began the journey to explore Việt Nam’s and my family’s complex histories, and their effects on my struggle to shape my identity, years passed before I could comfortably talk about things like the shame I felt about my family’s apartment or while sitting in that Leadership class at the Naval Academy. Looking back, I realize now that overcoming that shame has allowed me to receive and understand the experiences of many other people, and not just Vietnamese.

In 2017, I asked my mom to write down her recollections of our attempts to escape Việt Nam, which she did and then shared with me. I was 42 years old then, the same age Mom was when our family finally left our native land. That coincidental timing prompted me to dig deeper into our family’s experiences, as I was better able to empathize with my parents and to imagine some of the difficulties they must have faced in their own assimilation, both personal and professional. My mom once sat for a long interview with an academic researcher who was compiling stories about the Vietnamese diaspora, and she talked generally about the many adjustments that we individually and collectively needed to make. It was hard for all of us, she said. She did not provide any specific examples, unfortunately, but I would guess that for all immigrants assimilation involves a shedding of one’s identity. I use that metaphor knowing that it is a faulty one, for we cannot simply slip out of our skin and grow a new layer. We carry all of the layers with us, sometimes just beneath the new skin, and sometimes buried so deep that accessing them again would require an excavation.

For the sake of cohesion I have focused this story on my experiences and observations, but the discovery of my mom’s journals (following her passing in 2019) and other family documents granted invaluable glimpses into my parents’ lives, all the more relatable as I reached their ages at crucial junctures. The childhood shame and the guilt that later resulted from it have been transformed into a deep gratitude. My parents’ decision to part ways, possibly for good, while he was in prison; our dangerous escape attempts; the frustrating processes of applying for asylum and then immigration and of starting over twice as strangers in a strange land—they endured all of those things, and more, to give their children a chance at life.

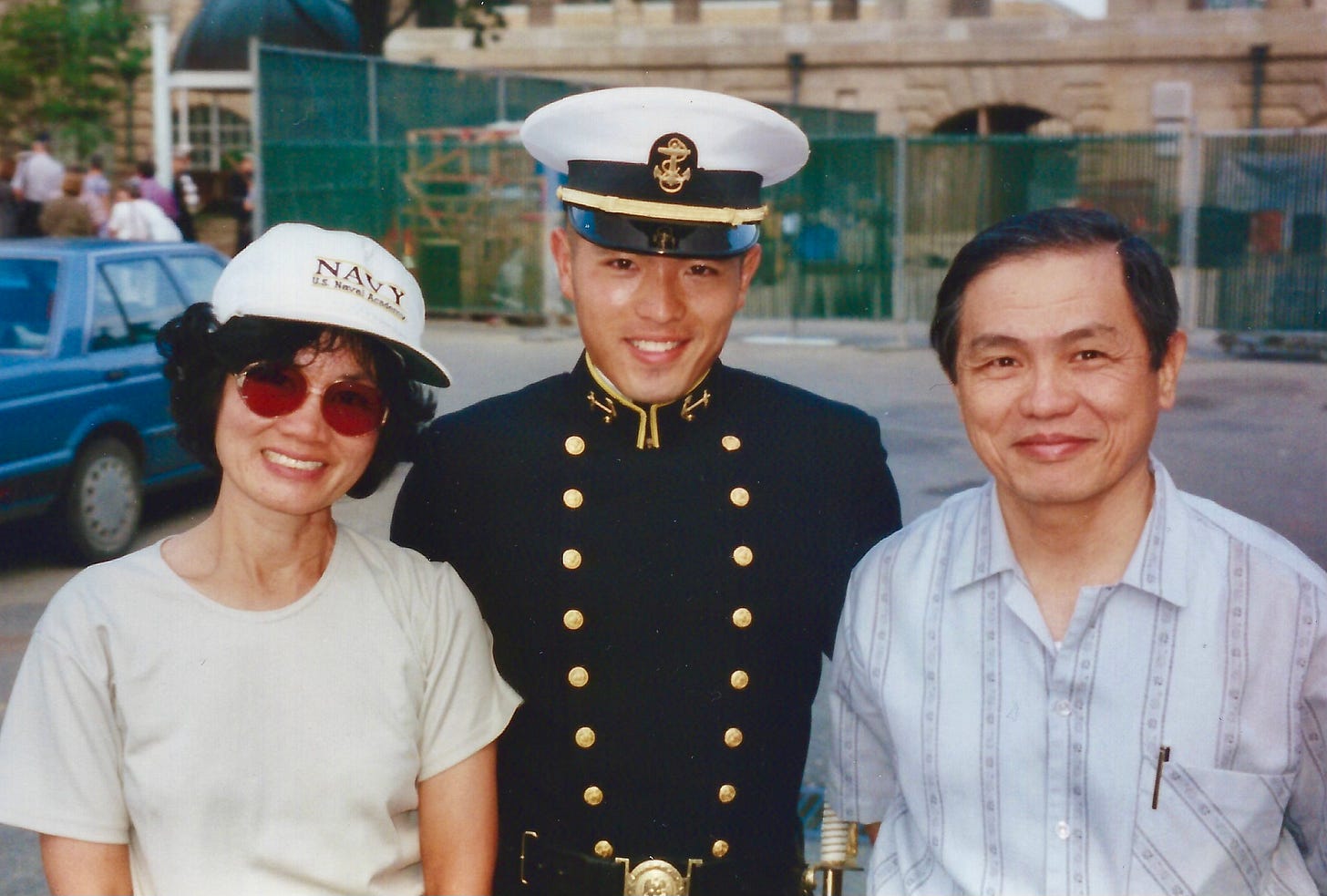

In the interview with the researcher, my mom talked about the joy and relief she felt when she became a U.S. citizen. Since 1975 and until then, she and my dad had been stateless people. Although we lived in reunified Việt Nam, the denial of basic rights rendered my parents non-citizens. Soon after they were eligible to do so here, my parents and siblings applied for and obtained citizenship. Because I was still a minor, I did not need to complete the process. Our generous laws allowed me just to wait and automatically become a citizen on my 18th birthday. I recall that, shortly before then, I felt a bit of uncertainty and nervousness when answering “No” to the question “Are you a U.S. citizen?” on the application to the Naval Academy. The form did provide a line of text for explanation, letting me write, “Citizenship imminent.” On Induction Day, with my parents among the crowd of witnesses, I was indeed solemn when I stood with my raised right hand and repeated the words “I solemnly swear that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States…” in chorus with 1,200 classmates.

To this day, I still get goosebumps each time a U.S. Customs agent returns my passport and says, “Welcome home.”

“Skipper Convicted Over Boat People.” New York Times, 24 February 1989, https://www.nytimes.com/1989/02/24/world/skipper-convicted-over-boat-people.html. Accessed 1 October 2024.

Norton, Michael. Email to Steve Le. 12 June 2023. Commander Michael Norton, USN, is the Associate Chair of the Department of Leadership, Ethics and Law at the Naval Academy.

Hilliard, Jacob R. and Christopher J. Goodale. Development of Case Studies for the Naval Academy NE 203 Ethics and Moral Reasoning for Naval Leadership Course. June 2022. Naval Postgraduate School, Master’s Thesis. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/trecms/pdf/AD1184919.pdf. Accessed 1 October 2024.

Right Here in My Pocket. “Voices from Oblivion: The Search for Bolinao 52, Part 1.” YouTube, 23 September 2022. Accessed 1 October 2024.

Nguyễn, Đức. “Interview with Bill Cloonan in Japan, tape 2.” Calisphere, University of California. https://calisphere.org/item/ark:/81235/d8c89h/?order=1. Accessed 1 October 2024.

Right Here in My Pocket. “Voices from Oblivion: The Search for Bolinao 52, Part 8.” YouTube, 11 November 2022. Accessed 1 October 2024.

“Vietnamese American Journey: Bolinao 52.” KQED, 10 April 2008. Accessed 1 October 2024.

Right Here in My Pocket. “Voices from Oblivion: The Search for Bolinao 52, Part 8.” YouTube, 11 November 2022. Accessed 1 October 2024.

Ramphele, Mamphela. Laying Ghosts to Rest: Dilemmas of the Transformation in South Africa. Cape Town, NB Publishers Limited, 2008, p.9.